Welcome to the latest monthly Endangered Alphabets feature about calligraphy and type design–in indigenous and minority writing systems.

Here’s the point. If a script exists only in historical documents, engravings, and inscriptions, it is all too easy to assume it is no longer in use, and the culture that created it has also been lost.

But if that script can still be seen, and what’s more, if it can be seen in new, interesting and creative forms, it’s a sign of life, energy, passion, commitment. It not only shows that unfamiliar script to the world in striking and memorable ways, it shows the user community that their traditional writing is still alive, and they have not been forgotten. Of course, communities also feel connected to their scripts because they are deeply familiar, so a designer or calligrapher has to walk a fine line between ancient and modern!

Our aim is to present the work of calligraphers and type designers who are bringing imagination and energy to endangered alphabets, by researching, understanding and acknowledging their traditions, but also adding the expressiveness and individuality that is one of the features of a living script. — Tim Brookes

By Mew Ophaswongse:

In type, the revival of historical designs often bring new life into them when designs from the past are adapted for the present context. In the case of Ranjana, a writing system used to write the Newar language, its revival connects the Newar people to their heritage that was almost erased. For political reasons, resources written in the script were destroyed. In the 1960s, the use of Devanagari as the only script in Nepal was enforced, resulting in an entire generation that never learned their indigenous script. Today, with Callijatra’s work, the script is being revived and taught in public spaces. The calligraphic, angular forms of Ranjana remain when used in different contexts and when written with different tools, liberating the script from its traditional roots while at the same time, preserving it for future generations.

Sunita Dangol is the co-founder of Callijatra, a collective of calligraphers promoting Nepalese scripts. She conducts open-air calligraphy workshops in public spaces as well as creates online teaching materials for Ranjana script and Newar language.

In her own words:

I grew up in Kathmandu and my mother language is Nepalbhasa, the indigenous language of the Newar community. I learnt Ranjana script later in life, about 3 years ago when my cousin brother, Ananda Maharjan informed me about its classes being held at Nepal lipi guthi.

Sunita Dangol’s calligraphy art

I had learnt calligraphy from my co-teacher from an after-school training center for children. Just seeing how the words were used and constructed really attracted me and I was glad to have learnt it. For Ranjana calligraphy, I learnt it at Nepal lipi guthi. I really wanted to learn the script when I saw the script in temples and older buildings. So, I jumped at the opportunity when it came about. Learning Ranjana really sparked a passion in me and I was constantly writing after classes, trying to develop my skills.

Me and a few like minded friends from lipi class really felt that bounding Ranjana classes in the four walls of a classroom was limiting its appeal and mainstream attraction. We really felt that despite its historical and calligraphic beauty, the way to learn Ranjana script is so limited. The class itself was difficult to access, too. Hence, we all reached a consensus that if people who are interested or can be interested to learn can’t reach the class, we will bring the classes to them. Hence the seeds of the idea were planted, which took a life of its own. We were able to do an open workshop at a Nepali New Year cultural event and the interest and attendance really encouraged us to keep pursuing this format. Callijatra was merely a “Facebook page” Ananda dai occasionally used to promote Nepali calligraphy during festivals, so we took that name and converted it into a mission to mainstream Ranjana script.

Callijatra’s teaching material

Yala Callijatra – Ranjana Lipi workshop at Manganbazar in 2018

Writing Ranjana with crayon

Writing Ranjana with bamboo reed

Different types of tools are used during these workshops. Each tool gives it a different texture, so to speak, but the core angular form remains the same. Regarding teaching, these tools are relatively inexpensive to make, you can take fountain pens you already have or bamboo reeds and cut them to get the angular nib. We have been providing bamboo brushes at open workshops and also showing how to make them to the attendees. Some really passionate trainees send us photos of their work and modification which truly validates our focus on openness spurring knowledge. Also, we wanted to show people that writing tools should not be an impediment in learning. Tools could be made with something as inexpensive as a broom, so we ensured we could make things as accessible as possible.

Callijatra is extremely fortunate to have contributors from a wide variety of fields. The quality of ideas and discussion is extremely rich due to this varied set of backgrounds. It also prevents us from seeing only one set of views and allows us to pool resources much more easily when needed. As we have members who have their own expertise like graphic design, photography, public speaking, app development — it becomes easier to pool our abilities together for any project despite us being a volunteer-driven initiative. So we have always been able to create various content be it workshops, posters, stickers, videos or technological solutions. The strength and energy of the contributors really has propelled Callijatra forward.

36th Ranjana Lipi Workshop and Live Calligraphy at Ramechhap, Bhangeri in 2019

36th Ranjana Lipi Workshop and Live Calligraphy at Ramechhap, Bhangeri in 2019Our future plans are to continue our workshops and also to move into language teaching avenues. We are starting with Nepal Bhasa first to see how we can innovate teaching on that end. Our hope is a mainstream appreciation and adoption of various indigenous scripts and languages that are now on the verge of endangerment in Nepal. Our work has also become advocacy in some aspects as schools have begun offering Ranjana Script classes and even government bodies have taken an interest in Nepal bhasa preservation and instruction in schools. This interest and renewed focus makes us believe our work is organically bringing substantial impact.

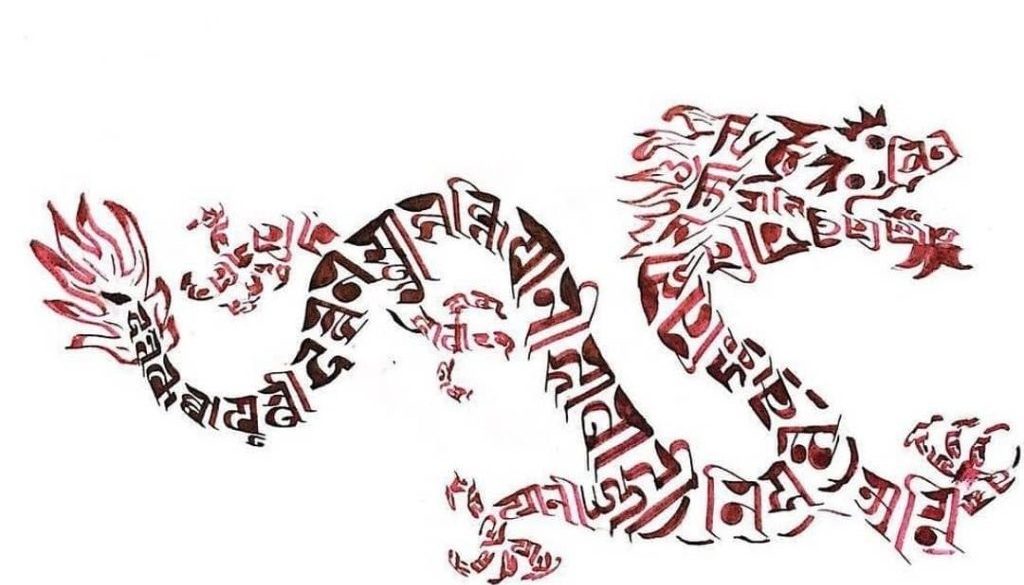

We don’t know if Callijatra’s work is revolutionary but it definitely has brought renewed interest in Ranjana both as a script and as an art form. I have always believed that culture shared is culture preserved, so to see people interested in the script, use it in designs, tattoos, art, inscription — all that shows that it is extending from being limited as a mere indigenous script. I think any use of Ranjana really excites me as it is a validation of our work. If I had to choose; two uses really jump at me. One, Ranjana’s use in murals and public art. The more people see Ranjana used beautifully and in public spaces, the more they are inspired to learn. Next, government bodies also have been writing the names of locations and their office buildings in Ranjana script. This really goes a long way in cementing the use of Ranjana as the government is also seeing it’s importance. Apart from that, seeing people customize the script, using it in clothes, jewelry and in their own way — it all shows ownership. The various merchandise we see people create is a show of the emotion that they have accepted Ranjana script as their own.

From the various workshops we have done across Nepal and internationally, we have found one constant — the joy in people’s face in learning to write again. It is a meditative experience and the physical activity truly brings you back to a time you began comprehending the world around you. With Newars themselves, this act is deepened by the fact that each stroke and letter they run, it connects them to a heritage many thought as on the verge of loss. To learn how to write, especially in their ancestral script it truly is a moment of connectedness. What we want to do is share this feeling and introduce the world to Ranjana and hopefully, other scripts that are beautiful but hidden.

Mew Ophaswongse writes: I’m a software engineer and typeface designer based in San Francisco, CA, originally from Bangkok, Thailand. I currently work at Wikimedia Foundation, where I build features for new Wikipedia editors. My educational background is in humanities and engineering—I have a B.A. in philosophy, comparative literature and cinema studies, an M.Phil in philosophy with focus on aesthetics and philosophy of technology, and a Master of Computer & Information Technology. I’ve always been fascinated by the intersection between humanities, design, and engineering. While studying philosophy, I became curious about about how the form and design of combinations of written characters generate meaning and emotional associations through the lenses of aesthetics, cultural studies, and philosophy of language. To me, type design brings all these disciplines together.

This post is sponsored by our friends at Typotheque, Letterjuice, and Solidarity of Unbridled Labor.

36th Ranjana Lipi Workshop and Live Calligraphy at Ramechhap, Bhangeri in 2019

36th Ranjana Lipi Workshop and Live Calligraphy at Ramechhap, Bhangeri in 2019