Designing Endangered Scripts, Part II: Aditya Bayu Perdana

Last month, we started a new monthly Endangered Alphabets feature about calligraphy and type design–in indigenous and minority writing systems.

Here’s the point. If a script exists only in historical documents, engravings, and inscriptions, it is all too easy to assume it is no longer in use, and the culture that created it has also been lost.

But if that script can still be seen, and what’s more, if it can be seen in new, interesting and creative forms, it’s a sign of life, energy, passion, commitment. It not only shows that unfamiliar script to the world in striking and memorable ways, it shows the user community that their traditional writing is still alive, and they have not been forgotten. Though of course communities also feel connected to their scripts because they are deeply familiar, so a designer or calligrapher has to walk a fine line!

My aim with this monthly feature is to present the work of calligraphers and type designers who are bringing imagination and energy to endangered alphabets, by researching, understanding and acknowledging their traditions, but also adding the expressiveness and individuality that is one of the features of a living script.

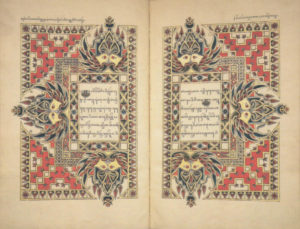

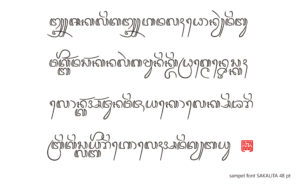

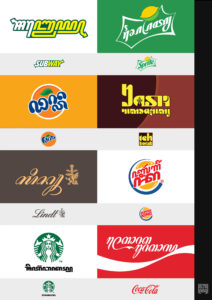

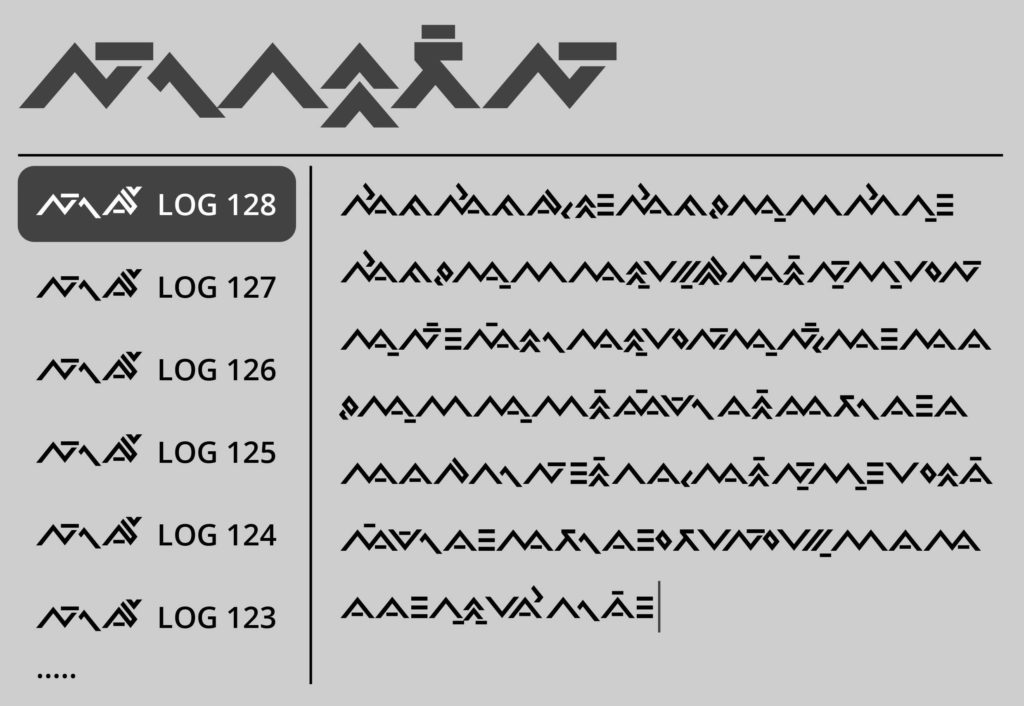

This month’s type designer is Aditya Bayu Perdana, from Jakarta, Indonesia, whose work, examples of which can be seen in this article, explores not only various expressions of the exquisite Javanese script, but other traditional scripts of Indonesia.

His interest in letterforms began in his senior year in high school.

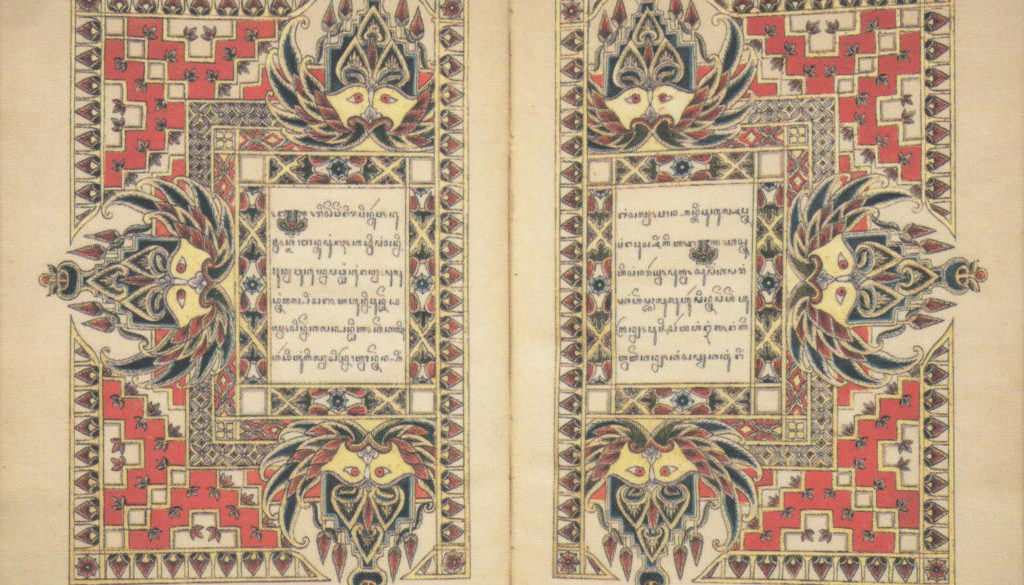

“We were assigned to write a paper about Indonesian culture and I researched about traditional literature. As it happens, my school’s library has a quite a decent encyclopedia section and one of them showed beautiful Indonesian manuscripts from the pre-independence days, such as this Javanese manuscript:

(For more information on this manuscript, see the footnote below this article.)

“Those examples got me interested in looking further on the internet. But unfortunately, I was rather disappointed to see that many contemporary samples were…. well, not up to par with the rich tradition that the encyclopedia describes. Many samples were rather crude, or only presented in tables with no indication of variety or interesting substantial usage. I was already interested in graphic design and (Latin) typography at the time, so i thought ‘How could I bring a bit of designing rigour into this?’

“So I tried learning it by myself, sleuthing around the internet, meeting a number of native users along the way and asked them a lot of questions, which I still do today.

“Whenever I learn a new script, the first thing I do is look is for a manuscript written in it.

“It is unfortunate that many Indonesians today have only ever seen traditional scripts on tables, but rarely seen the script in its natural context: inscribed on palm leaf, or adorning illuminated manuscripts. A table is very helpful, of course, to get the bearings but the way a script ebbs and flows in a paragraph is sometimes lost in a table where all the letters have been neatly justified in rows.

“I always try to collect samples (from the internet) of various text, preferably with provenance and high res, to get a sense about the ‘skeleton’ of a letter. This is important to me to learn which part is integral to the identity of the letter and which parts are scalable into decorative strokes. I try to analyse the strokes by trying to write them myself before trying onto digital platform.

“Now that I think about it, my process more or follows to what Ben Mitchell called `designing like a native,’ at http://www.fontpad.co.uk/designing-like-a-native/.

“Indonesian scripts were never standardized, so each text naturally varies somewhat, and part of my enjoyment in learning about them is sometimes finding a quirky or unique scribal hand that can be applied to modern design.

“Unfortunately, since Latin has mostly replaced traditional scripts in Indonesian everyday use, many people only encounter them briefly in elementary school and are not inclined to use them afterwards.

“With the general public rarely seeing or using their script, let alone historic samples, it can be quite hard to introduce variety. Whenever I use a historically attested style, some people may be very confused by it. But if I stick to the version taught in schools (which is often simplified), then my work would not be different from those same bland samples that the textbook provides. It’s a delicate balance.

“Most responses to my work have been positive, fortunately, but I do have to explain things in quite a lengthy manner. Explaining and distinguishing between `wrong,’ `correct,’ `acceptable variant,’ and `uncommon variant’ can be a real minefield for me.

“How to engage interested people, encouraging them to learn more, but not dissuading them when errors (inevitably) occur is not something that I have entirely grasped.

“I strive to make my explanation nuanced and contextual, because many people unfortunately are taught in the simple dichotomy of right and wrong way in writing traditional script without acknowledging stylistic variants and such. This sometimes prevents them from learning more or making interesting choices in their applied design.

“And for the future? Honestly, I don’t know. I’d like to write a book about this some day!”

Footnote on the pre-independence Javanese manuscript (https://blogs.bl.uk/asian-and-

“It is a fragment of palm leaf/lontar manuscript from Hans Sloane’s collection in the British Library. As you may know, palmleaf manuscripts need to be rewritten every decade or so since the material is susceptible to damage in tropical climate. Old palmleaf manuscripts such as this one (no date, but we know it is before 1753) are quite rare. Use of palmleaf manuscript has a long track record in Indonesia, especially in Java and Bali. When paper began to be introduced in Java around the 15 to 16th century, many Javanese writers switched to paper and the use of lontar only persisted in a few places, most notably in Bali where palmleaf tradition still lives today.

“This palmleaf is a fragment of Kakawin Arjunawijaya, a genre of epic poem (Kakawin) in Old Javanese language. At the time of the writing, the Javanese and Balinese had not deviated much from each other so this hand can be (aesthetically speaking) seen as a crossroads of both scripts. The Kakawin is preserved within Balinese literary circle, and while Sloane labeled his collection as ‘Javanese lontar,’ it is unclear whether he meant it is purchased in Java, written in Java, or written with the (old) Javanese language.

“But origins aside, my main draw to it is its beautiful script.”

You can follow his work on Instagram. Anyone interested in traditional Indonesian scripts in general might want to check out this book.

This post is sponsored by our friends at Typotheque, Letterjuice, and Solidarity of Unbridled Labor.