Another New Script for Mesoamerica

If you like chocolate, you ultimately owe it to the Aztecs, who would drink a cocoa-based beverage called chocolatl. You may also have heard other words, such as Tenochtitlan (the capital of the Aztec Empire), Quetzalcoatl (an Aztec deity, after whom the pterosaur Quetzalcoatlus is named), or atlatl (a device used to throw spears). All those words come from Nahuatl, a language that has been spoken for many centuries in Central America.

As far as writing goes, up until the early 1500s the Nahuatl language had a form of pictographic notation, but it was not really used to write texts, only signs indicating certain places, persons or events. After the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors, with their imposition of the Latin alphabet, Nahuatl was written in both prose and verse, as well as the first Spanish–Nahuatl dictionary, the “Vocabulario en lengua castellana y mexicana”, by Alonso de Molina, in 1555.

Different Latin-based orthographies have been used, the most recent one proposed by the SEP (La Secretaría de Educación Pública de México). However, using the Latin alphabet to write Nahuatl has several problems. First of all, the letters are used in ways that won’t necessarily make much sense if you happen to speak Nahuatl more so than Spanish. On the other hand, having a more regular spelling—such as the SEP standard—can lead to awkward-looking names, such as “Ketsalkoatl,” especially if you are already familiar with the more usual “Quetzalcoatl” form.

Other issues include having digraphs such as TZ, TL, and CH for commonly occurring phonemes —that leads to most words having a cumbersomely large amount of letters— as well as syllable boundaries not being clear — one may not know if a given sequence of letters corresponds to the ending of one syllable or the beginning of the next.

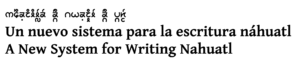

In order to address those and many other points, Edward Trager, a software engineer who is also a digital typographer, has developed an abugida (also called alphasyllabary) to be used when writing Nahuatl. As he explains on his website:

“During the Fall semester of 2015, several colleagues and I took an introductory class in modern Eastern Huasteca Nahuatl offered through the Center for Latin American & Caribbean Studies (LACS) at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA, and taught via web technologies by Prof. Eduardo de la Cruz Cruz of the Instituto de Docencia e Investigación Etnológica de Zacatecas (IDIEZ) at the Autonomous University of Zacatecas in Zacatecas, Mexico.

“During the semester, I developed an effective abugida for writing Nahuatl in my own notes and flashcards. An abugida is a type of syllabary or alphabet in which consonants carry an inherent unwritten vowel, often an /a/. Additional signs are used to change the vowel quality as needed.

“In devising this new abugida, I borrowed some functional ideas from Tai Tham and other Indic abugidas of Southeast and South Asia which I had previously studied.9, 10 Because of this, some of the letter shapes look superficially similar to Tai Tham letters, but most of them are actually based on Latin letters and share sound values with the Latin letters from which they are derived. For other Nahuatl phonemes, such as the very common /tɬ/ (tl), I invented unique letter shapes. In all cases, I made sure that each letter could be written using not more than two or three joined strokes without lifting the pencil off the paper. In other words, I made sure that the letters were simple and could be written quickly. I also made sure that the letters and vowel signs were sufficiently distinct from one another to avoid confusion when written hastily.”

Basically, all consonants have an inherent vowel A (e.g. KA), so they can work as a syllable on their own. Should the vowel of that syllable be different, that’s when you write a small symbol above the consonant (e.g., KA + E becomes a KE); if the syllable also contains a final consonant, it is written below the main letter (e.g., KE + S becomes KES).

The script has some other advantages, too. Take for instance “caltlamachtiloyan” (school), which requires 17 Latin letters in the traditional orthography. In the New Nahuatl Orthography, all six syllables can be written using… six letters, plus a few additional signs for the syllable-final consonants as well as some of the vowels. As a bonus, syllable boundaries can be clearly identified, so a reader always knows whether a TL—a digraph (in the Latin orthography) which happens to have its own one-letter symbol (in this writing system)— belongs to the end of a syllable or to the beginning of the next.

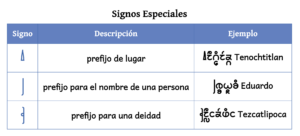

One last feature of the script is that, while it doesn’t distinguish between uppercase and lowercase forms, it uses three special symbols to indicate names referring to places (e.g. Tenochtitlan), persons (e.g. Eduardo), and deities (e.g. Tezcatlipoca).

The New Náhuatl Orthography is currently being used by some native speakers and is also undergoing digitization. While it is currently possible to use it in a digital font format —such is the case with the project’s webpage—it is yet to be proposed for inclusion in Unicode.

Walter T. Sano

This post is sponsored by our friends at Typotheque and Rosetta.